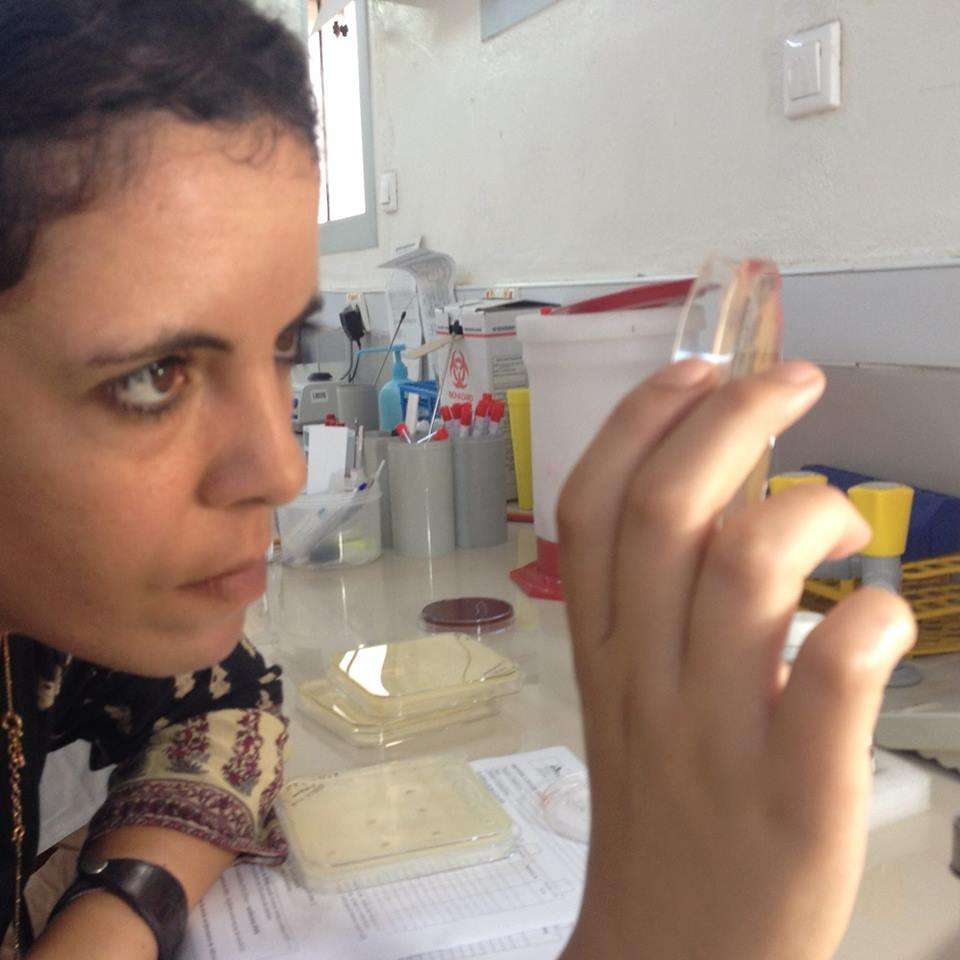

What is your role at MSF?

My job is to help Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams access diagnostic tools, mainly by opening microbiology labs and determining what diagnostic tests standard MSF labs should include. Properly testing people for infections is a key part of prescribing them the appropriate antibiotic and preventing the likelihood of antibiotic resistance (ABR).

I have been involved in opening labs for MSF in places like Mali, Jordan, Yemen, and Central African Republic (CAR). Today we have 11 projects that have access to microbiology labs—five are run 100 percent by MSF, and six are operated in collaboration with national Ministries of Health or private institutions.

Why does work on antibiotic resistance matter?

Antibiotic resistance is a universal problem, but the solutions for MSF are different because the resources we have in the types of places we work are generally lower than what is available in Europe or the US. We cannot see ABR as a geographically localized problem, as [globalization means that] bacteria are now more easily traveling to other places—now it is "bacteria without borders” and “resistance without borders.”

Antibiotics were one of the most important medicines discovered—a gamechanger in the history of infectious diseases. But today we are running out of antibiotic options because bacteria have become resistant to so many of the current drugs, and companies haven’t invested in creating new ones. Prescribing the best antibiotic for a patient based on their microbiological results is important to ensure that we are treating patients properly and in a timely manner, but it’s also important in terms of public health that we are not creating more and more resistance by giving broad-spectrum antibiotics without having a targeted approach in terms of treatment.

What’s MSF’s strategy to tackle antibiotic resistance?

We have three pillars we believe play the most important roles in curbing resistance: increasing diagnostic capacity, improving infection prevention and control (IPC) in our facilities, and promoting the rational use of antibiotics so people only get the antibiotics they truly need when and for the length of time they need them. In our projects, we have microbiologists and infectious disease specialists, we have staff members responsible for hygiene and infection control, we have pharmacists who supervise access to antibiotics—and then, of course, we have the management team who is also involved in making sure we don’t lose sight of these pillars.

Why is tackling resistance a priority for MSF?

MSF’s focus on ABR began in the Middle East when we started receiving war-wounded patients with open fractures that were more susceptible to infections like osteomyelitis, a bone infection. From the first day—the first patient—we had to face this problem, because the bacteria we were dealing with were highly resistant to many drugs. This was partly because of the overuse of over-the-counter antibiotics in places like Jordan, Iraq, and Yemen.

We started asking ourselves, “Why is the patient I am treating with antibiotics not responding? Maybe there is [drug] resistance?” Curbing resistance is also important where patients are malnourished, have higher rates of severe burns, or have malaria or HIV, since when you are immunosuppressed you have a higher risk of getting an infection and needing antibiotics.

What are the biggest challenges fighting ABR in low-resource settings?

If clinicians see that their patients are not responding— and they don’t have tools to diagnose the exact infection and identify which antibiotic would be most effective— their temptation is to switch to a more powerful antibiotic. While doctors may think that’s the best or only option to save the person in front of them, we want to avoid this kind of blind prescription of antibiotics because it can lead to more resistance.

Then you have the problem of hygiene and infection control in health facilities. We have to train staff to enforce IPC measures, like properly washing their hands between patients. Staff also need to know how to implement a proper isolation area for patients with drug-resistant infections. You need to know that patients infected with the resistant bacteria are isolated and that those bacteria are not going to spread across the hospitals. This is, to be honest, one of our biggest challenges—more than the diagnostic challenges and more than the rational use of antibiotics.

How can MSF make an impact when this is such a complex, multidisciplinary, global problem?

It is true that it is not enough to have only MSF working to curb resistance. I think that at the level of our hospitals we can only have an impact on the direct clinical management of our patients. But that’s why one of our advocacy strategies is to share our experience with other actors in order to have more and more people and organizations involved in this.

We are large and, in some areas, we are the only actor that has the ability to adhere to those three all-important pillars [to tackle ABR] in the same facility and show that this model works. Another way MSF has an impact is resistance surveillance. In Mali, for example, we worked to have our microbiology lab recognized as a surveillance laboratory to monitor resistance in the region. I think MSF can have a huge impact if our work can help shape and reinforce national surveillance systems.

Innovation: New tools to diagnose and treat drug-resistant infectionsASTapp: MSF is developing a smartphone app to help diagnose antibiotic resistance in low-resource settings. Diagnosis of infections can be challenging in many of the places MSF works, due in part to the fact that there are usually few laboratories or specialists who can read and interpret antibiograms—tests used to determine how susceptible bacteria are to different antimicrobial medicines. ASTapp would allow non-specialists to more easily analyze and interpret antibiogram pictures on their smartphones or tablets. This information can help them determine exactly which antibiotic a person should get, reducing the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the chances of resistance. The project was recently awarded a Google Artificial Intelligence Impact Challenge grant of $1.3 million. MiniLab: To address the problem of a lack of laboratories and trained staff in low-resource and emergency settings, our teams are testing a new concept in Haiti called the MiniLab. Without the tools and expertise required for a proper diagnosis, people aren’t always given the right antibiotic for their particular infection. The MiniLab is a small-scale, portable structure that can be easily assembled where needed and used by non-experts with relatively little training. If the pilot in Haiti is successful, MSF will launch a second trial in a different part of the world in 2020. MSFeCARE: MSF uses a tool called MSFeCARE—or electronic clinical algorithm and recommendation— to improve the quality of care and more appropriately prescribe antibiotics to treat acute illnesses in children from two months to five years old. Using a tablet application, eCARE guides health professionals through a step-by-step, point-of-care assessment of the patient’s symptoms and signs. The app provides expert recommendations and standardized procedures to diagnose and treat acute illnesses. So far, eCARE has been used in remote areas where diagnostics aren't widely available, including in MSF projects in Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania, Chad, and Central African Republic. |